So, you’ve heard that DSLRs produce better pictures than bridge cameras? This guide has everything you need to know to decide which camera wins the Bridge vs DSLR toss up.

Firstly, not all DSLRs are created equal, so the answer will of course depend on which DSLR we’re talking about. While there’s clearly no way that even the best bridge camera is going to match a top-of-the range, full-frame DSLR such as the Nikon D810 on image quality, it’s also true that an entry level DSLR like Canon’s EOS 100D doesn’t offer an enormous increase in resolution over one of the larger-sensored bridge cameras.

It should be obvious from this, then, that image quality is not the sole difference between one format and the other, in fact there may not even be all that much difference at all depending on the exact models in question. Or, just as equally, the difference might be huge.

Clear as mud.

Which is better then? Well, one reason why it can initially seem so tricky to make any sense of all this is partly to do with precisely the question ‘which is better?’ Sometimes its a valid question to ask. More often than not, though, the question would elicit more helpful answers if it were re-worded somewhat: ‘which is going to be the best for my needs?’

So, before we start, you should try to get as clear an idea as possible of what it is you plan on doing with your new camera, And in answering this question, it’s not only important to consider your present needs, but what you might want to achieve with photography in the future.

With that said, lets go back to the basics.

Jump To Section

What is a Bridge Camera?

On the plus side, and to compensate for this, bridge camera lenses are usually capable of zooming from very wide to very narrow points of view, offering a great deal of flexibility. So while you can’t remove the lens, you’re unlikely to ever have reason to want to either.

Bridge cameras are generally quite small and portable when compared with DSLRs.

What is a DSLR?

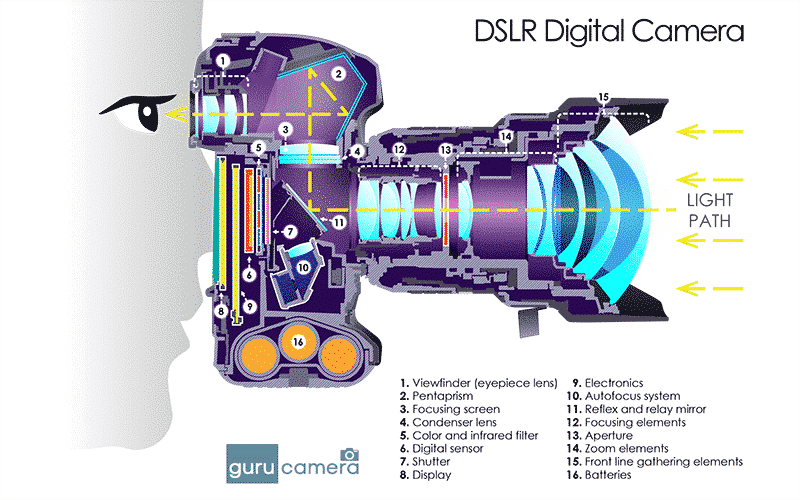

The reflex part is the mirror that reflects the image through to the LCD screen or optical viewfinder so that you can see what it is you’re taking a picture of. Then, when you press the shutter, this mirror flips out of the way and the light is redirected to the camera’s sensor, thus capturing the image.

Presently DSLRs are the pinnacle of consumer and professional photographic technology, generally offering greater image quality, speed and battery-life than bridge cameras do. They also take interchangeable lenses and various other accessories and offer an even greater amount of control than is generally possible on a bridge camera.

DSLRs are generally much bigger and heavier than bridge cameras.

Recommended: The 9 DSLR Cameras in 2021

Image Quality

Image credit: Matthew Bailey, Must Do Canada – Things to do in Banff

While image quality is determined by several different factors, the single most important one is the size of the camera’s sensor. A full-frame DSLR has a sensor that measures 36x24mm, other (usually cheaper) DSLRs have sensors measuring only 24x16mm. Either of these options is going to produce a higher resolution image than the much smaller (typically 6.17×4.55mm) sensors usually found on bridge cameras (although recently we’ve seen several bridge models released that feature 1-inch sensors).

It’s also important to remember that sensor size doesn’t only dictate image resolution: the smaller the sensor, the poorer the camera’s performance will be in low lighting conditions. This means more ‘noise’ in your photographs. Not good.

For these reasons, some photographers look on bridge cameras as just glorified compacts. Sure, you get much more flexibility and control than you would with a point and shoot, but the sensors generally aren’t much bigger or better. Whereas a point and shoot is really just for snapping memories in auto-mode, with a bridge camera you have considerably greater control over the outcome of the photo, and therefore it’s totally possible to produce quite technically advanced and creative shots.

The question remains, however, whether it’s really worth going to all this effort to make great photos, if in many cases their resolution is likely going to be insufficient for anything beyond looking at on screen or printing quite small.

As mentioned above, however, some newer bridge cameras, such as Canon’s sturdy PowerShot G1 X Mark II, have much larger sensors that produce images approaching DSLR-like quality.

Problem solved?

Not quite. Bridge cameras are also known by the alternative name of “superzooms” for the extreme variation in focal range many of them offer. For anyone wanting maximum flexibility in a highly portable, lightweight camera, this may sound like a convenient feature. For example, the Sony Cyber-shot DSC-H400 comes with an astonishing 63X zoom lens, the equivalent of which on a DSLR would probably need a separate carry-case in which to lug it around.

So, yes, some bridge cameras can offer a similar resolution to DSLRs, but with the added advantage of a long built-in zoom.

Sounds perfect.

But hold on a second! The operative word was “can”. What about in practice though? Well, for sure, some will, but only when you’re not using the zoom lens fully extended. And it’s precisely these mega-zooms that garner much of the criticism directed towards bridge cameras, as sadly the longer the zoom is, the poorer the quality of image it is likely to produce.

Under good lighting conditions, and with the zoom on a moderate setting, some bridge cameras can give very good results. In fact plenty good enough for most peoples’ purposes. But probably not when you’ve got the zoom on a long setting – which kind of defeats the purpose of choosing a camera with a built-in zoom in the first place. Indeed you might well ask what the point of a mega-zoom is if you spend most of your time trying not to use the more extreme focal length settings for fear of compromising image quality.

At this point you’d have done better just to have bought a DSLR with a small and lightweight fixed lens (or one of the retractable ones that Nikon and other brands offer, if bulk is a major concern) and just used this. At least you’d know the results would be of consistently high quality, even if you can’t zoom in.

On the other hand, if you really do need to shoot with an exceptionally long or wide lens some of the time, then a DSLR is still going to be your best bet – at least if you value image quality. There are plenty of legitimate reasons why someone might need to use a telephoto or mega-wide angle lens to get a particular shot, but as a somewhat OT aside, I can still remember the advice given to me by an old darkroom boffin when I was just starting out in photography: “the best zoom is your legs”. I.e. don’t rely on technical gimmickry if you can just take a few steps forwards or backwards. Especially if it will compromise image quality. So, before making your decision, think carefully about whether you really need such a long zoom lens in the first place.

Finally, if image quality is important to you, then you’ll definitely want to be capturing your images in RAW format, not as JPEGs (even JPEGs shot on the highest quality setting have been compressed and consequently contain less information than a RAW file). There are very few DSLRs that cannot capture in RAW. However, when it comes to bridge cameras, the percentage of models that do not offer RAW capabilities becomes much greater, so make sure that you do your homework before purchasing.

A great option for capturing RAW files, and on a top-quality 1-inch, 20 megapixel sensor, is the Canon G3 X.

Indeed, for maximum image quality in the bridge camera sector you’d be wise to concentrate your research on Canon, Fujifilm and Panasonic’s offerings.

For example, with its 1-inch sensor, the Panasonic LUMIX DMC-FZ1000 could be a good solution for anyone looking for great image quality on a portable camera with only a moderately long zoom. However, when you consider that the Panasonic costs more than a good entry-level workhorse DSLR such as the Nikon D3400 – and is actually not that much smaller – it’s clear that high-resolution imagery in a compact body comes at a high premium.

A cheaper option that still offers pretty good image quality, but with a considerably lower pixel-count, is Canon’s PowerShot SX50. Be aware though that the newer SX60 actually offers inferior image quality to the SX50, so save your money and go for the older model.

Image Stabilization

Some people are under the misconception that only bridge cameras offer image stabilization.

While technically speaking this can actually be true in a way, as DSLR camera bodies do tend not to provide image stabilization, there is in fact a good reason for this: it’s because in the DSLR format the stabilization is more frequently built into the lens.

Furthermore, lens-based stabilization is usually more effective than a system built into the body. Therefore, if you are concerned about camera shake and worried that you risk losing out on a helpful feature if you go the DSLR route, rest assured that on this count a bridge camera offers no advantage.

Speed

A DSLR will be faster than a bridge camera on pretty much every level: whether in focusing on the subject or in shooting a rapid succession of images. Indeed, with bridge cameras there is frequently a delay between pressing the shutter and capturing the image. This means that a bridge camera is not the best choice if you’re hoping to take pictures of sports or other moving subjects.

Weight and Size

As mentioned earlier, with their interchangeable lenses, mirrors, powerful processors etc., DSLRs are invariably much bigger and heavier than bridge cameras. Although there are some quite slim and lightweight DSLRs out there now, realistically speaking, none of them are going to be able to slip unobtrusively into your shirt pocket. Most bridge cameras will. Although as sensor sizes have increased on bridge camera, so too has their size, consequently, on this front, the differences between the two formats are getting less and less significant as time goes by.

Price

While we might automatically think of a bridge camera as the cheaper option, a good quality bridge can easily cost several times more than an entry-level DSLR. As case in point, the excellent Sony Cyber-shot RX10 costs over a grand. Meanwhile, some very reasonably priced entry-level DSLRs are of extremely good quality (see the previously mentioned Nikon D3400). As it turns out, then, there’s not even necessarily an economic reason to side with bridge cameras in the end.

Although, conversely, it should be noted that a very top-of-the-range DSLR such as the 50-megapixel Canon 5DS costs more than twice the price of Sony’s RX10, and that’s without the lens. So, again, it just depends on which models we’re talking about.

Other Considerations

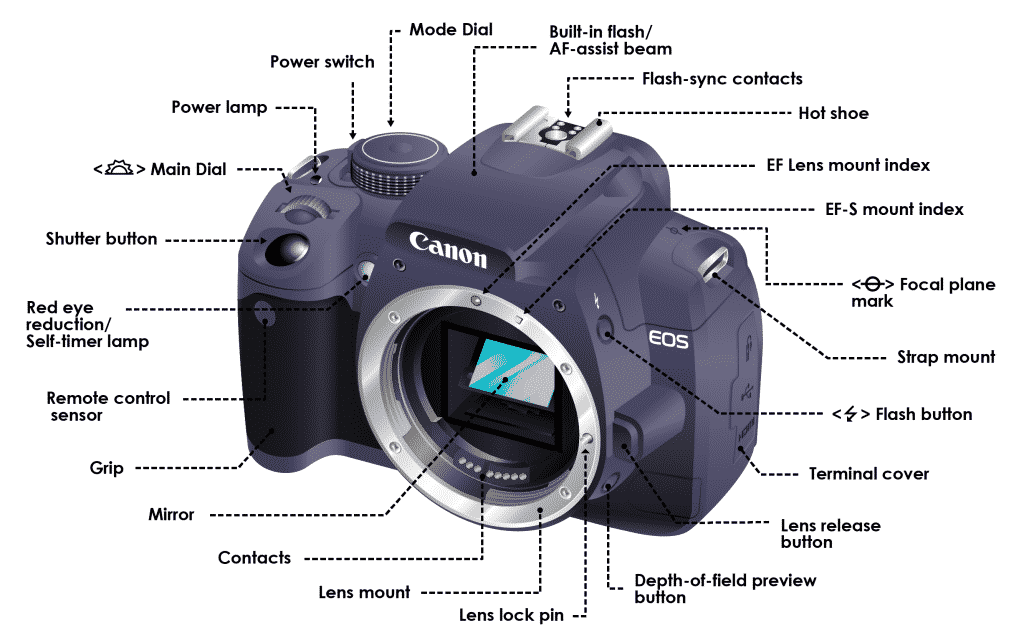

If you think you might want to experiment with flash photography at some point, make sure you get a camera with a hotshoe, as this will allow you to add an external flashgun in the future. An external flash will be more powerful than any built-in flash and can be bounced or modified with accessories for a more flattering effect. Pretty much all DSLRs come with a hotshoe, whereas many bridge cameras do not.

Battery life will be considerably longer on a DSLR than with a bridge camera. Even the cheapest DSLR is usually good for 400+ shots from a fully charged battery, rising to 1,000+ as you move up the line. Meanwhile 400+ shots is about the best you can hope for from a bridge camera before the battery will need switching.

When it comes to shooting video, bridge cameras generally perform pretty well. Although it pays to research this side of things thoroughly, as video features can vary massively from one make and model to the next. The same goes for DSLRs to a certain extent, although most are now fully capable of capturing HD 1080 and offer much greater flexibility and control over the process than a bridge camera will.

Whether a camera comes with internal Wi-Fi seems to vary just as much for DSLRs as it does for bridge cameras. For example, Nikon’s excellent D3400 comes without Wi-Fi capabilities, whereas Panasonic’s LUMIX DMC-FZ1000 comes with.

In order to save space and cut down on weight, bridge cameras frequently lack an optical viewfinder, instead relying entirely upon the rear LCD display or an electronic viewfinder. Conversely, DSLRs normally come with an optical viewfinder, although the viewfinders on cheaper models tend to show only about 95% of true image area.

As we’ve already noted, full-frame sensors produce the best images, but this is less true today than it was a few years ago: smaller cameras are now capable of producing amazing quality images. However, one area in which full-frame clearly still has the upper hand over smaller formats (including Micro 4/3 DSLRs, as well as bridge cameras) is in permitting narrower depth of field. This means that if you’re hoping to get that nice effect where, say, the subject’s eye is pin sharp but the background and foreground nicely soft and blurry, then you should forget all about going for a bridge camera.

Of course, the cheapest full-frame DSLR will cost you more than even the most expensive bridge camera. However, there are a few cheaper routes in to full-frame shooting, such as the Canon EOS 6D, that are actually not that much more expensive than some bridge cameras, so don’t just assume that full-frame is closed to you due to budget restraints: if you’re serious about photography and want to learn with the proper tools, full-frame may turn out to be the better choice in the long run, even from an economic point of view, as it’ll save you from having to upgrade at a later date once you’ve inevitably outgrown the bridge camera.

Conclusions

All things considered, there’s really only one area in which we can conclusively say that a bridge camera offers any major advantage over a DSLR, and that’s in terms of weight, size and convenience. However, depending on your needs, this point alone may be more than enough to convince you that a bridge camera is in fact the right way forward.

Certainly there’s no point in buying a fantastic camera if in the end you never take it anywhere with you because it’s so heavy and unwieldy. That just means a lot of beautiful, high resolution photographs will remain untaken. Probably better to buy a mediocre camera and use it regularly than invest in a state-of-the-art bit of kit that just ends up gathering dust on the shelf.

There are many bridge cameras that can easily sit in your pocket or purse at all times without you even noticing that they’re there, until you need them. If most of the time you’re going to be using the camera outdoors, in daylight, taking typical sightseeing or landscape photos, then a decent bridge camera will likely do you very well – in which case you might as well save yourself the bother of carrying around all the unnecessary weight and bulk of a DLSR.

On the other hand, as the cameras in smartphones get better and better, bridge cameras begin to lose their advantage. Why carry a second lightweight camera if you already own an acceptably good one in the form of your phone? Furthermore, if you see yourself as likely becoming more serious about photography in the future, then eventually you will need to purchase a DSLR. If that’s the case, why postpone the inevitable?